Shaan Syed

English Paintings

9 October – 9 November 2024

Vardaxoglou, London

Vardaxoglou is pleased to present a solo exhibition with Shaan Syed (b. 1975, Toronto, Canada). It is Shaan Syed’s second solo exhibition with the gallery and features new works from Syed’s recent ‘English Paintings’ series (2020–2024), which explores the artist’s personal history spanning British India, Pakistan, England, and Canada. An extended text by the artist accompanies the exhibition.

For further information please contact info@vardaxoglou.com.

Shaan Syed was born in Toronto, Canada in 1975 and lives and works in London, UK. He holds an MFA from Goldsmiths College in London (2006) and a diploma in Fine Arts from OCAD in Toronto (2000). Recent solo exhibitions include presentations at Bradley Ertaskiran (Montreal), Vardaxoglou (London), and Kunsthalle Winterthur (Winterthur). He has participated in numerous group exhibitions in venues such as The Power Plant (Toronto), Aga Khan Museum (Toronto), Art Gallery of Peterborough (Peterborough), and the Roberts Institute of Art (London). Syed is the recipient of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Award (2013) as well as the Arts Council of England and Canada Council for the Arts project Grants. His work is part of the permanent collections of the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), Art Gallery of Peterborough (Peterbrorough), UBS Art Collection (Dubai), MoMa Library (New York), Goldsmiths College (London), RBC Art Collection and TD Canada Trust, among others.

English Paintings

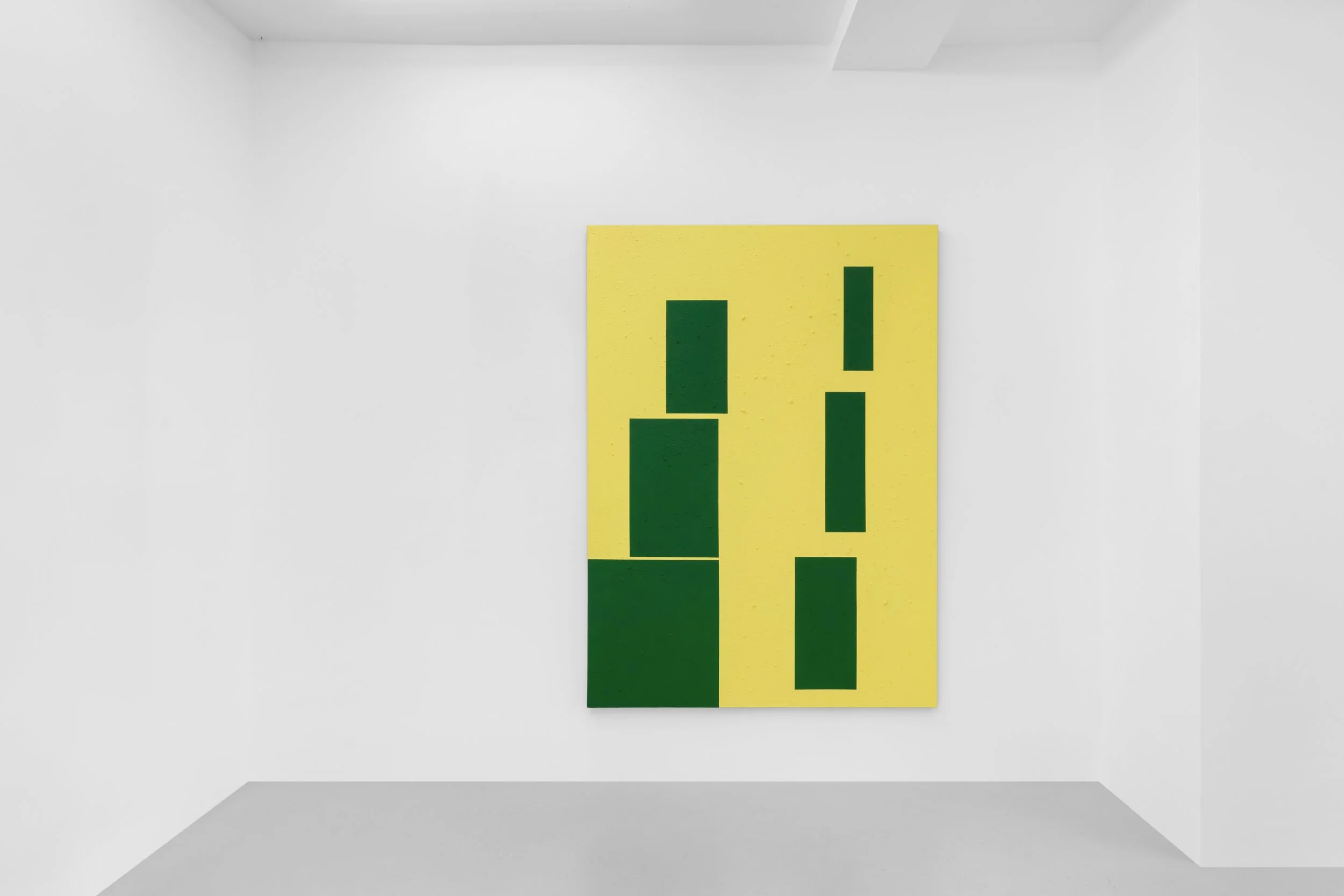

“I've been making these English Paintings. There are two sets: “EP1” and “EP2”. The EP1 paintings are on heavy jute, with gravel and stones stuck on and green rectangles painted in different sizes. I made these in 2020 during Covid. The EP2 paintings are from this year, 2024, with collaged paper and oil paint on linen. The paper has a reverse monoprinting thing happening with rubber plants, with lots of green everywhere.

Green is the colour of grass, 1960s Denby pottery, and the Pakistani flag. Rectangles are basic, like flags and paintings. The EP1 rectangles remind me of mosque prayer areas. I’ve been to mosques, and they all have a common footprint. The floors are always open and free of furniture so people can assemble in rows and face Mecca for prayer.

Before this, I was painting abstracted minarets. I called them “Minaret”, “Double Minaret”, “Split Double Minaret”, or “Disintegrating Split Double Minaret”, depending on the amount of abstraction. The EP1 paintings are a change in looking across a distance to looking at the floor. When you see a minaret from far away, it says, “Islam lives here”, which makes it a symbol. Looking down, you see a map.

I had thought I should wait for the right time to show the EP1 paintings. Covid was weird. Later, I started making green collage paintings, cutting and pasting paper with drawings of rubber plants. It felt good, like finding my wild side. The colour and surface reminded me of chalkboards. Eventually, I decided to show both sets together.

Gardens and plants are important to the English. There's a long history of recording and categorising plants. It's a whole science. Plants from around the world were brought back to England and given Latin names. The rubber plant, “Ficus Elastica”, was one of the first from South Asia. I drew the one in my flat and researched its history. Now I see rubber plants everywhere: in other people's homes, interior design magazines, shop windows, and art. I like that the plant has a hidden history, a trajectory.

Drawing and painting can be so different. Drawing is immediate, like something primal. Painting is slow and full of deliberate choices, even if it sometimes seems fast and furious. People talk about sincerity and immediacy, but I think we need to slow down. The EP2 paintings came from drawing with a paintbrush handle, creating marks on paper. It’s a kind of printing with no original. Cutting and collaging the paper was the final step, making drawing into painting.

I keep thinking of Andy Warhol's flower paintings. The last time I stood in front of one, it really hit me. He turned an image so benign into not just a symbol of the era, but an emblem of its collapse. All that hope and optimism of the 1960s just disintegrating into nihilism. It's all there in his flowers. Now, I'm wondering, could the rubber plant speak to another kind of collapse? Can it signify the end of a western-centric way of looking at art?

When Muslims first came here, they prayed at home. Over time, they gathered and built mosques. Now there are mosques all over England. My father left Pakistan for England in the late 1950s, joining his brother in Bolton. This was after they fled India to the newly formed Pakistan because of Partition. In England, they weren't religious. They partied and met English girls. English women found them exotic and exciting. They must have brightened up a dreary post-war social scene.

London is full of old council housing and brutalist buildings from the post-war era. A lot of them were built in the spaces left by German bombs. They were meant to offer people a step up into modern living. They can look beautiful on sunny days but sad on dreary ones. Today, the old council homes are often rented to new immigrants, or converted into chic open-plan spaces by new owners.

My parents moved to Canada after meeting in London. Canada was a fresh start, away from old entanglements. My father worked hard and bought a house in the suburbs. Our home was decorated with stuff from Pakistan, like engraved wood plaques with Quranic verse, brass filigree table tops and block-printed fabrics, mixed with other more typical suburban family decor. As I grew older, everyone seemed to be filling their homes with exotic things, but now, moderation is key.

I found a book from 1938 for home decorating called "A Historical Color Guide" by Elizabeth Burris Meyers. Each page consists of colour blocks arranged in rectangles to show how much of each colour to use in a room. The arrangements have titles like "French, Empire" and "Primitive, Modern". I like these titles because they show how people wanted to think about their homes back then. If my paintings were classified in this way, they might be called “Coronation, Brutal” or "General Needs, English Mosque".

I’ve been in London for twenty years. It’s home now. When I came, it was the financial capital of Europe. Now, it’s struggling with that identity. My own story spans British India, Pakistan, England, Canada, and back to England. In two generations, England went from superpower to something else. People are figuring out what England should be now.”

Shaan Syed

Installation Views

Selected Works

-

Shaan Syed

EP 2.01, 2024

oil and paper collage on linen

190 x 137 cm

74 3/4 x 54 ins -

Shaan Syed

EP 1.03, 2020

oil and gravel on linen

190 x 137 cm

74 3/4 x 54 ins -

Shaan Syed

EP 2.08, 2024

oil and paper collage on linen

190 x 137 cm

74 3/4 x 54 ins -

Shaan Syed

EP 1.04, 2020

oil and gravel on linen

190 x 137 cm

74 3/4 x 54 ins

Artist Page